While any length of treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD) often yields significant benefits, prior analyses of Community Medical Services SDOH (social determinants of health) data have shown that patients who undergo treatment for a longer period see significantly larger improvements. After compiling SDOH data for nearly two years, we can more accurately analyze the outcomes of our longer-term patients.

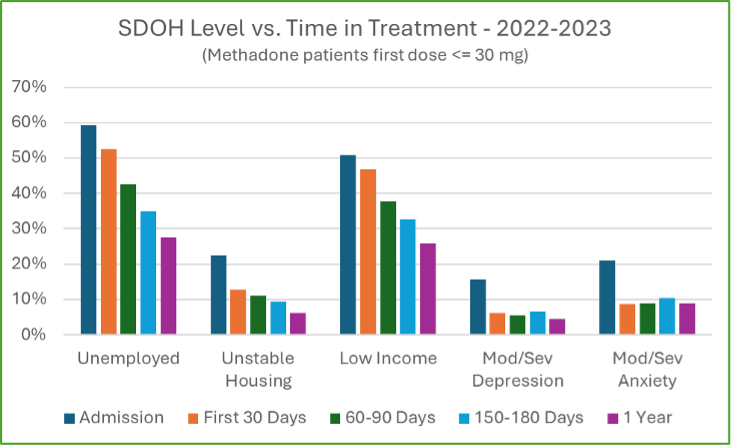

Our original study was based on shorter-term data but still showed that patients improved significantly with more prolonged treatment. These are the results of our first study, which may have some built-in bias, as those who stay in treatment longer will have better SDOH levels on admission:

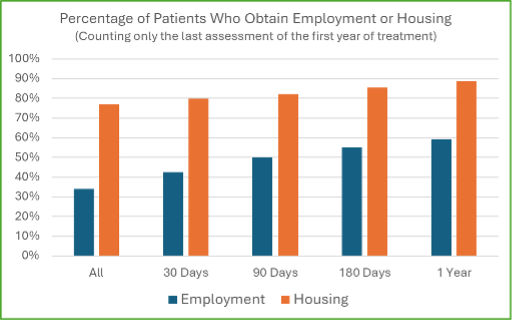

However, now that we have almost two years of SDOH data, we can update our analysis and correct the above graph.

An Updated Analysis: The Results of 2 Years of SODH Data

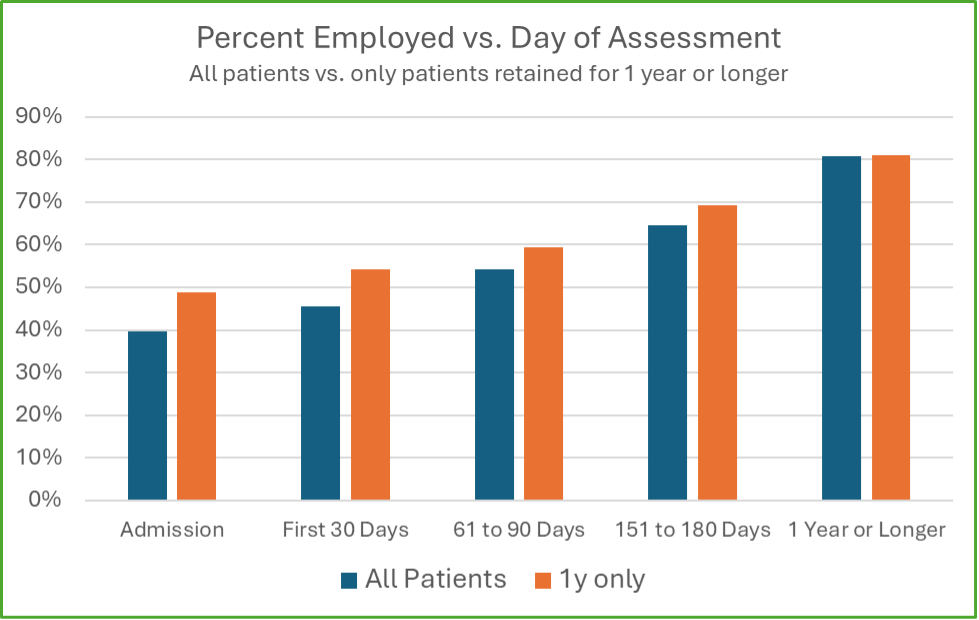

Similar to the first graph, the blue bars indicate that for all patients, about 60% are unemployed on admission, and many of those patients will be employed for one year if they continue their treatment. The above graph includes all patients, while the first study showed only methadone patients with an initial dose of 30 mg or less. Additionally, while the blue bars comprise all patients, only those still in treatment are included in the longer time frames.

The orange bars are corrected for the admission SDOH bias. Only patients who stayed in treatment for one year or longer are included in the series, meaning that the admission results only show responses for patients who stayed in treatment for a year. There is higher employment in this group, which tracks with our initial observation that patients employed on admission have a higher chance of continuing treatment for a year.

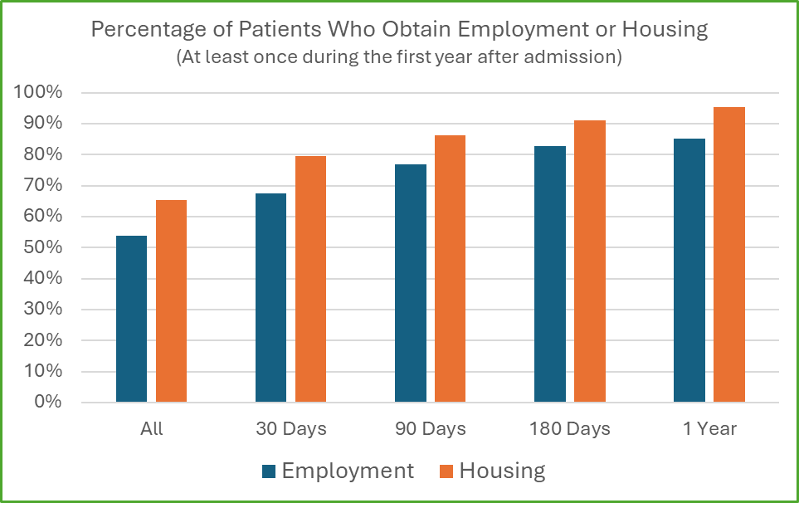

With our increased range of data after 2 years, we also explored the percentage of patients who obtain employment or housing after certain treatment periods. At a high level, this is what our updated study found:

- 54% of those who walk into a Community Medical Services clinic for the first time and are unemployed will get a job within a year, no matter how long they stay in treatment.

- 65% of those without stable housing who visit a clinic will obtain housing within a year, no matter how long they stay in treatment.

- If the individual stays in treatment for 30 days, these numbers increase to 67% and 80%, respectively.

- If they stay in treatment for 90 days, the percentages rise to 77% and 86%, respectively.

- If they stay in treatment for an entire year, the numbers rise to 85% and 95%, respectively.

It’s important to note that few patients with an active OUD who are unemployed will obtain a job without treatment. Still, our data shows that anyone with an OUD who walks into one of our clinics will increase their chances of obtaining employment within the next year to over 50%. The longer they stay in treatment, the more likely they will find a job and obtain housing.

How was the CMS Data Analyzed?

Our SDOH data can be analyzed in many ways, and it can be complex to determine how it should be reviewed and displayed. However, it’s essential to do so in ways that are easy to explain and make intuitive sense. To help this process, we provide additional details of our data and different ways it can be explained below.

What is Collected in the Data Warehouse?

Community Medical Services started collecting SDOH data in all CMS clinics in July 2022. At the end of every medical intake or follow-up appointment, the medical provider fills in a pop-up window that asks five questions about SDOH, primarily focused on employment, housing, income, and emotional state. Our analysis focuses on two of these factors – employment and housing status.

How are Employment and Housing Assessed?

Before the progress note can be saved in Methasoft, our advanced clinic software, the provider must choose from four options for each of the five questions concerning SDOH. For employment, these options include:

- Employed, student, caregiver, disability – full-time or retired

- Employed, student, caregiver, disability – part-time

- Intermittent employment or odd jobs

- Unemployed

To simplify the analysis and make the results more intuitive, the first two categories are considered employed, while the last two are considered unemployed. Housing questions are similar, including four different options for each of the 5 SDOH questions:

- Independent housing

- Stable but dependent on friends or family

- At risk of losing housing or unstable/at risk

- No stable housing – shelter, car, “couch surfing,” or homeless

For the housing questions used in our analysis, the first two categories are considered “housed,” and the last two are considered “unhoused.”

Who is Selected for the Analysis?

All patients new to CMS and admitted between August 1st, 2022 and February 28th, 2023 were included in this analysis if they had at least one SDOH assessment logged within the first 7 days after their admission. We selected this particular period because by August 1st, 2022, all CMS clinics completed SDOH assessments at all provider intake and follow-up visits. For patients admitted before February 28th, 2023, we can determine their outcomes for an entire year after their admission based on the data we have accumulated today. This period saw 5,551 total new patients admitted for their first CMS episode. Of these 5,551 patients, 5,241 were qualified for analysis after having at least one SDOH assessment within their first week.

For employment analysis, all patients who were unemployed on admission were included, which totaled 2,625 patients. To determine their employment status on admission, all SDOH assessments done between treatment day 0 and 6 were scanned. If any of these indicated employment, the patient was designated as employed on admission. If all assessments indicated unemployment, they were categorized as unemployed on admission. The same process was used for housing analysis, with 962 patients selected for the unhoused group.

The SDOH Outcomes of Long-Term Treatment: Our Findings

For each patient in the group, all SDOH assessments done during their first year after admission were scanned. If any of these indicated employment, the patient was designated as “employed” at some point after admission. The same process was used for housing. However, if no assessments indicated employment or housing, the patient was classified as unemployed and/or unhoused.

When all patients were included, our analysis showed that 54% of the patients who were unemployed on admission had at least one assessment with employment during their first year after treatment. Similarly, 65% of all patients who were unhoused on admission had at least one assessment during their first treatment year that indicated stable housing.

Whether or not they dropped out of treatment prior to 1 year, all patients were included in the initial analysis. This means that once they left treatment and were no longer being assessed for SDOH, they were assumed to be unemployed and unhoused. If a patient dropped out of treatment and then returned, any employment and/or housing assessments done within a year of the first admission were included in the analysis.

To create subgroups, we implemented filters to restrict the group to those who continued in treatment for 30, 90, 180, and 365 or more days. These were the findings:

As we discussed earlier in this study, our data highlighted three significant findings:

- If the individual stays in treatment for 30 days, these numbers increase to 67% and 80%, respectively.

- If they stay in treatment for 90 days, the percentages rise to 77% and 86%, respectively.

- If they stay in treatment for an entire year, the numbers rise to 85% and 95%, respectively.

The far left-hand blue and orange bars consider all the unemployed and/or unhoused patients and their likelihood of being employed/housed over the next year. Each longer interval only considers the patients who continued treatment for that time or longer. This graph clearly shows that as patients stay in treatment longer, their likelihood of obtaining employment and housing increases.

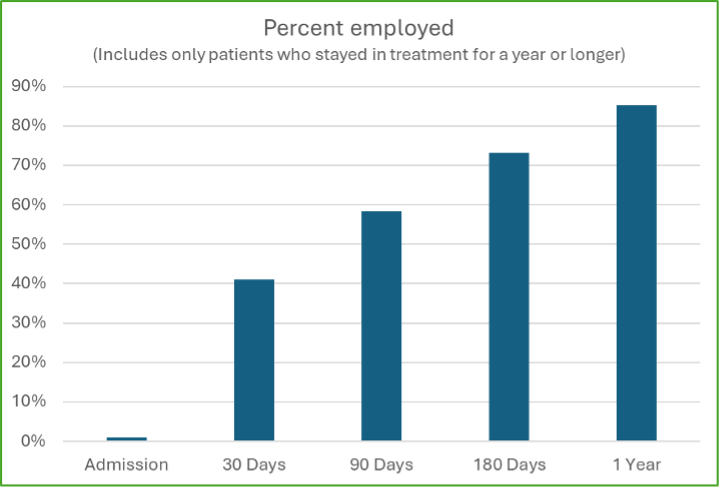

We also analyzed patients who stayed in treatment for a year or more and were unemployed on admission. In the graph below, we highlight the length of time patients are required to have the first assessment showing employment on file. By including only patients who stayed in treatment for a year or longer, the graph removes any selection bias due to the length of treatment.

The Final Assessment: Further Analysis

It may be argued that a patient who had only 1 assessment showing employment or housing during their first year of treatment should not be designated as obtaining meaningful employment or housing. If a patient was unemployed on admission, subsequently was employed, but then lost that job and was unemployed for the rest of the year, they likely shouldn’t be considered employed during the year. We utilized more stringent criteria to filter out these scenarios.

We completed a secondary analysis using only the last SDOH assessment patients completed within their first year after admission. For this to be positive, the patient would have to obtain a job and/or housing at some point during the year and still be employed and/or housed when they were last assessed. If a patient stayed in treatment for a year, this assessment would be up to 364 days after admission, but if they dropped out before the 1-year mark, it would be before they left treatment.

Since the criteria are more stringent, the results of this analysis have lower percentages than the one above. However, even with the stricter criteria, the percentages of patients who say improvements in employment and/or housing status are significant. These are the results:

Limitations of the SDOH Study

While the results are significant, there are a few limitations. First, the measurement of employment and housing, performed by the medical provider, leaves room for interpretation. The SDOH assessments are done only at medical intake and follow-up appointments, meaning some patients will have more assessments than others. This data is also only based on dosing data, meaning that prescription patients are excluded. While it does include transfers from outside clinics if they completed an admission SDOH assessment, it does not include guest dose patients, as they do not routinely get medical intake or follow-up appointments and, therefore, do not have any SDOH assessments on file.

Additionally, patients were included no matter which modality they were treated with, whether they opted for methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone. While patients who moved from one CMS clinic to another were tracked using global ID, those without assigned global IDs (about 3%) were excluded.

This analysis also assumes that anyone who is unemployed throughout treatment and drops out before one year will remain unemployed throughout the year, and some patients who are unemployed and drop out may get jobs during the year after admission. We have no clear way of assessing them after they drop out unless they return during the year and are assessed again. If some of the patients who dropped out got employed, then our estimate of 54% may be low.

Finally, while 54% of everyone who walks into the clinic unemployed will be employed the following year, we don’t know what percentage of patients would become employed if they did not come to the clinic. There is no way to obtain this data, as a randomized trial would be unethical, and there is no way to match patients to potential patients who do not visit a CMS clinic. Therefore, this analysis does not have a “control” comparison group. However, we can reasonably assume that most people with severe OUD using fentanyl (which makes up most of our intakes) will continue to be unemployed without treatment.

CMS Notes Significant Improvement in Patients Who Stay in Treatment for 1 Year or More

Our SDOH data shows that CMS patients improve dramatically in multiple areas of social health when they stay in treatment for a year or more. In particular, almost all of them obtain employment and/or housing within a year of admission. After a full year of treatment, our study found that 85% of patients could obtain a job while 95% could secure stable housing.

We know from scientific literature that medication-assisted treatment decreases mortality, which fulfills CMS’ primary goal of “keeping people alive.” However, our data shows that we are also highly effective in our secondary goal of improving patients’ lives and “helping them thrive” by supporting them through their recovery journey so they can secure stable jobs and housing.

If you or a loved one are struggling with opioid use disorder, you’re not alone. Community Medical Services provides compassionate and expert medication-assisted treatment to help individuals reduce their dependence on opioids, achieve long-term recovery, and lead a more fulfilling life. To start your recovery journey, find a CMS clinic near you and contact our supportive team today.