How do you view someone with an opioid use disorder (OUD)? What words would you use to describe that person? What types of emotions does that person generate from you?

These can be difficult questions, but their answers are crucial to our ability to overcome the opioid crisis in our country. Why would your opinion of a person with OUD be important?

“The primary reason people don’t seek treatment for their OUD is stigma,” says John Koch, director of Community Engagement at Community Medical Services (CMS). And he should know, having fought the battle of OUD for many years before getting the help he needed to thrive, living the life he wanted to live.

“It’s hard for people to admit they have a problem and need help for fear of being labeled, shamed, discredited,” says Koch. “People with OUD don’t feel like they can talk about it because they’re so used to being judged. But that’s why people die. They need to be able to talk about what’s going on without judgment. They need to be seen for who they really are: fathers, mothers, daughters, sons …. People in need of help,” he says.

CMS Chief Medical Officer Dr. Robert Sherrick is all too familiar with the impacts of stigma. “Stigma is a cycle

that’s difficult to break,” he says. “Self-stigma is the type patients are susceptible to. This self-blame often impedes their treatment.” Stigma also exists in the medical profession. Errors in treating patients happen when the focus is influenced by stigma instead of by pursuing the best patient outcomes, says Dr. Sherrick. The criminal justice system is yet another example where stigma makes it difficult for people with OUD to get treatment. And the cycle continues.

Science shows that an opioid use disorder isn’t about weakness, personal or moral failure, or even a lack of willpower. Many people in the behavioral health field see addiction as a disorder of motivated behavior, meaning, once someone’s brain chemistry has been destabilized by opioids, a person’s motivation changes and they can become trapped in a continuous cycle that only professional treatment, counseling, and a strong support system can help them overcome. Understanding that OUD isn’t always a choice can be a first step towards stopping the stigma, says Koch.

“There’s a lot of debate right now about whether OUD is a disease or a learned behavior,” says Dr. Sherrick. “It’s both.”

“It really comes down to education,” says Dr. Mark Stavros, CMS Medical Director for Arizona. “We need to think of OUD as a medical condition and not just a behavioral disorder. There’s a medical component and a behavioral component,” he says, comparing it to diabetes. “You can’t give a diabetic insulin and then tell them to eat whatever they want.”

Koch believes the way to stop the stigma is through empathy and education. “Just take one second to think about what that person is going through,” he says. “We need to remember that a substance use disorder is not a moral failing. It happens to people from all walks of life, not just someone experiencing homelessness or low-income individuals. It happened to me, and it was the caring hand of a police officer that got me the help I needed.”

Dr. Stavros agrees wholeheartedly. “The most important thing we can do to help people with OUD is to exhibit empathy,” he says. “People can learn empathy over time from colleagues, mentors, and clients who teach us along the way. We must get beyond our biases.”

To emphasize the importance of empathy when treating people with OUD, Dr. Sherrick referenced a study that showed counselors with a high level of empathy were highly successful in treating patients with OUD, while results from those counselors who showed no empathy toward patients were worse than if the patients had no counseling at all. “The study showed that unempathetic counselors could actually cause patients harm,” he said.

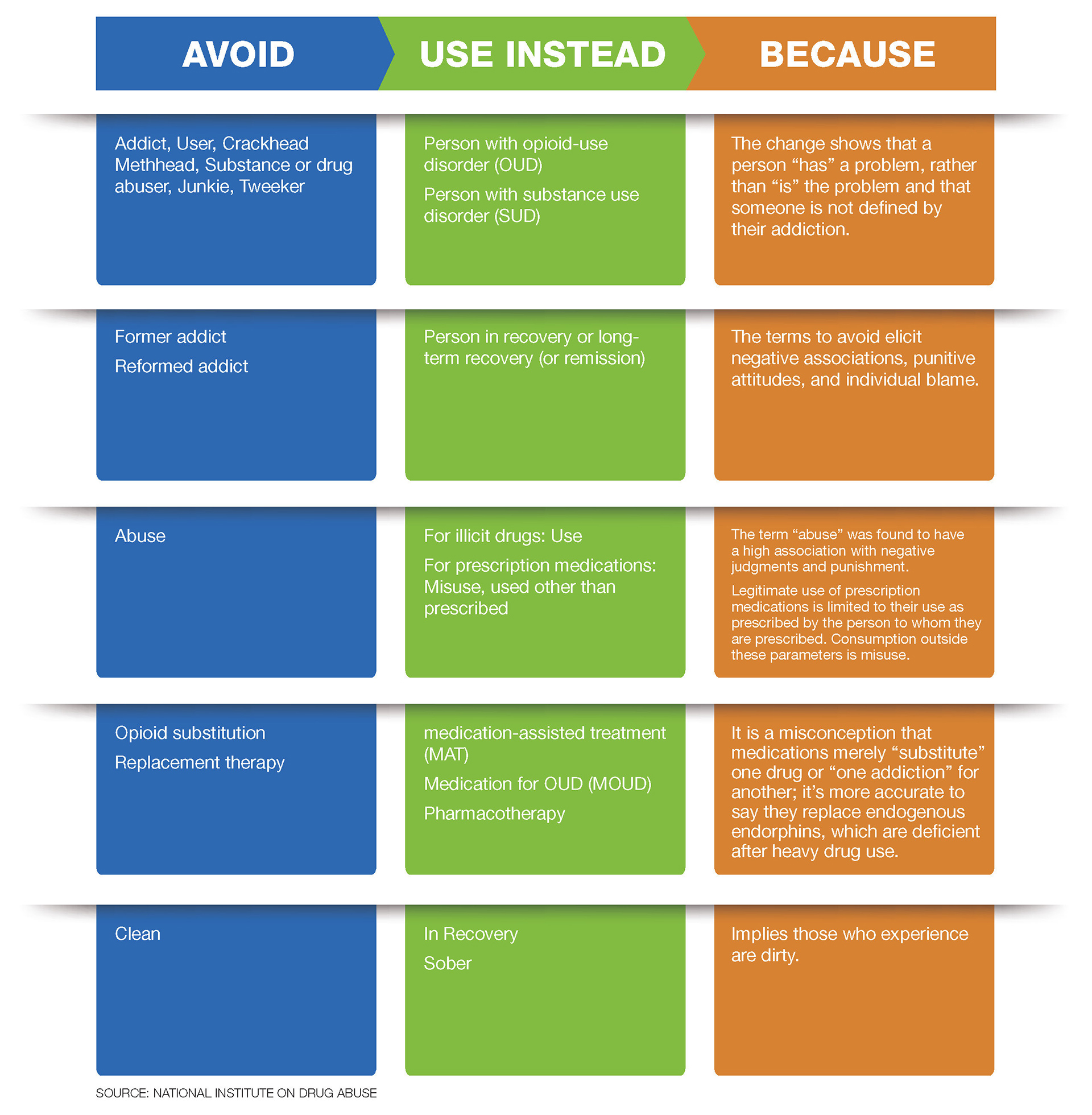

Avoiding certain words will also significantly help destigmatize substance use disorders (SUDs). When talking about people with a substance-use disorder, use non-stigmatizing language. Here are words to avoid, terms to use, and why.

If you encounter a friend or acquaintance who uses stigmatizing language, Koch suggests reminding them that they are referring to someone who is hurting and needs empathy and support. Stigmatizing language actually prevents that person from seeking and getting the help they need.

A critically important aspect to addressing the opioid crisis and helping those one-in-three people with a substance-use disorder is to make treatment more accessible by meeting people where they’re at. Recovery for people with OUD is possible, but they can’t do it alone.

“Access to treatment is a huge step toward recovery,” says Koch. More local programs are needed for people to enter treatment and stay in treatment. But efforts to open treatment centers in key areas are typically met with resistance from residents, making it difficult for CMS and other organizations to reach those in need.

While Koch agrees CMS has a role to play in educating residents on how their programs can be beneficial to the community, the stigma that surrounds the issue creates a “not-in-my-backyard” mentality that is hard to overcome. Being more accepting and compassionate as a community can go a long way towards removing the barriers to the treatment of OUD.

The opioid epidemic is a serious public health crisis, as deaths from opioid use disorder continue to rise. Stigma towards people with OUD remains a substantial barrier preventing people from getting the care they need.

Stigma occurs all around us and in places we may not even realize. Awareness and education are key as hospitals, the healthcare industry, first responders, lawmakers, business leaders, and other stakeholders take a leading role in creating positive change.

CMS believes one step towards breaking down stigma is to incorporate training and education regarding OUD and other substance-use disorders into medical school curriculums to reduce stigma and to provide better services for those with SUD.

But for each of us, there are simple things we all can do to help take better care of people with an opioid use disorder; better words we can use; treatments we can offer; and loving and empathizing attitudes we can foster.