How SAMHSA’s Final Rule Changes Are Improving Opioid Use Disorder Treatment at CMS

In April 2024, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) implemented its first significant update to opioid treatment regulation in over twenty years. The changes, known as the Final Rule, represent a significant shift in how opioid treatment programs (OTPs) operate across the United States. These new regulations make treatment more accessible and less burdensome for patients by allowing for increased take-home doses of medication and higher initial dosing of methadone.

At Community Medical Services (CMS), we have begun implementing these updates where state regulations allow, and early data shows encouraging results. In applicable states, patients no longer must visit the clinic as frequently, which simplifies their treatment process and, in turn, improves retention rates. While more data is still needed, these initial findings suggest that SAMHSA’s changes are already making a difference in the lives of those battling opioid use disorder.

Understanding SAMHSA’s Rule Changes

On April 2, 2024, SAMHSA made significant updates to the regulations that govern over 2,000 opioid treatment programs across the United States. These regulations, known as “42 CFR Part 8,” were established in the 1970s and hadn’t seen substantial changes in over two decades. The new updates modernize opioid treatment practices and provide patients and healthcare providers with more flexibility. These updates simplify the treatment process, increase accessibility, and ultimately improve retention in opioid treatment programs.

Among the many changes outlined in the Final Rule, three stand out as particularly important:

- Extended Take-Home Doses: SAMHSA increased the number of take-home doses allowed for patients early in treatment. For example, within the first 14 days, patients can receive up to seven days of medication at home.

- Higher Initial Methadone Doses: Initial methadone dosing increased from 30 mg to 50 mg, which helps stabilize patients more quickly, especially those with high opioid tolerance due to substances like fentanyl.

- Urine Drug Screen Adjustments: The Final Rule now specifies that the presence of drugs detected on urine drug screening does not necessarily limit take-home medications unless their use increases the risk of an overdose.

Increased Take-Home Doses: Breaking Down Barriers to Treatment

One of the most significant updates in SAMHSA’s Final Rule is the increase in allowable take-home doses for patients in OTPs. Previously, patients were required to come to the clinic frequently to receive their medication, which could create a major barrier to treatment for those with work, family obligations, or transportation issues. Now, the Final Rule allows for extended take-home doses, giving patients more flexibility in treatment management.

The rule outlines the following take-home schedule:

- During the first 14 days of treatment, patients can receive up to 7 days’ take-home doses.

- From 15 days of treatment onward, patients may take home up to 14 days’ worth of medication.

- After 31 days of treatment, take-home supplies can extend to as much as 28 days, depending on the discretion of the OTP provider.

Medical providers use six criteria to determine if a patient qualifies for take-home doses, including factors like the absence of behavioral problems or recent substance abuse, regular attendance, and the patient’s ability to store the medication safely. However, as noted in the Final Rule, many of these criteria are difficult to assess during a patient’s initial intake, leaving much of the decision to the provider’s judgment.

At Community Medical Services, we have implemented a minimum triweekly dosing schedule in states where the regulations allow, except for cases where daily clinic attendance is necessary for the safety of the patient. Instead of having to come to the clinic every day for months, patients can start out coming just 3 days a week to the clinic to talk to a nurse and take their dose and be given doses of medication to take home for self-administration on other days. This approach significantly reduces the burden of daily clinic visits, allowing patients more autonomy while maintaining safety protocols. Even patients who test positive for illicit substances or miss dosing days will not fall below tri-weekly dosing in most cases.

The early data shows that these changes reduce barriers to treatment and improve retention, as patients have greater flexibility in managing their recovery while still receiving the support they need from their treatment programs.

Higher Initial Methadone Doses: Faster Stabilization for Patients

Another critical change in SAMHSA’s Final Rule is the increase in the allowable initial dose of methadone for patients beginning treatment. Previously, the maximum first dose cap (30 mg) often left patients, particularly those with a high opioid tolerance, struggling with withdrawal symptoms during the early days of treatment. The new regulations allow for an initial dose of up to 50 mg, giving medical providers greater flexibility to meet the needs of patients with higher opioid tolerances, particularly those exposed to fentanyl.

This change is especially critical in today’s environment, where fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, is contributing to increased opioid tolerance among many patients. Higher initial dosing means patients can reach a therapeutic dose quicker, reducing their discomfort and the likelihood of dropping out of treatment early due to inadequate symptom management.

At CMS, we have implemented these new dosing guidelines where allowed. In states that do not yet permit a 50 mg initial dose, our policy allows for the second day’s dose to reach 50 mg, even if the patient’s first dose was limited to 30 mg. By closely monitoring patients’ opioid tolerance levels and adjusting their induction dosing schedules, we can stabilize patients more effectively and ensure they are receiving the care they need as quickly as possible.

Our early data suggests that higher initial doses contribute to improved treatment retention. Patients are more likely to stay engaged in their recovery when they aren’t battling severe withdrawal symptoms during the critical first days of treatment. As we continue to gather data, we expect this trend to demonstrate further the positive impact of SAMHSA’s new dosing guidelines.

Urine Drug Screen Changes: A New Approach to Take-Home Eligibility

SAMHSA’s Final Rule also significantly changed how urine drug screens (UDS) determine eligibility for take-home doses. Under the previous rules, patients who tested positive for any illicit substances were restricted from receiving take-home medication. However, the new guidelines recognize that not all substances carry the same risk of overdose. Therefore, the presence of certain drugs should not automatically limit a patient’s take-home medications.

The updated rule states that take-home doses should only be restricted if the presence of an illicit substance increases the risk of overdose. For example, stimulants like methamphetamine or cocaine, which do not cause respiratory depression, do not acutely raise the risk of opioid overdose and thus should not limit the patient’s access to take-home doses. This shift acknowledges the complexities of substance use disorder. It focuses on reducing the risk of harm rather than enforcing punitive restrictions.

CMS continues to evaluate UDS results for opioids, fentanyl, benzodiazepines, and other high-risk substances. However, the presence of stimulants or non-life-threatening substances no longer automatically affects a patient’s take-home status. This more nuanced approach allows us to focus on the patient’s overall safety and progress in recovery, rather than penalizing them for every positive UDS result.

This change has already shown positive effects in states where it has been implemented. Patients feel more supported in their recovery journey, knowing that occasional setbacks will not drastically impact their treatment plan. Early data suggests that this approach encourages greater retention in treatment programs, as patients are more likely to stay engaged when they are not facing overly harsh consequences for non-life-threatening drug use.

How CMS is Implementing SAMHSA’s Changes

At CMS, we have proactively implemented the SAMHSA Final Rule changes where state regulations allow. Our approach focuses on balancing patient safety with reducing the barriers to treatment, ensuring that the updates benefit our patients and their recovery outcomes.

In states where extended take-home doses are permitted, CMS has made significant progress in rolling out these changes. Triweekly dosing—where patients come in only three times per week—has become the new standard. This means that most patients, even those who might test positive for stimulants or miss some clinic days, are not required to visit the clinic more than three times a week. For patients who meet certain stability criteria, the option to advance to weekly clinic visits is available after just two weeks of triweekly dosing. This provides immense relief to patients who previously struggled to balance daily trips to the clinic with their other responsibilities, such as work or family.

CMS is also implementing the updated dosing guidelines. Where states allow, patients may be started on an initial methadone dose of up to 50 mg, ensuring quicker stabilization for those with high opioid tolerance. Even in states where this is not allowed, CMS permits a second-day dose increase to 50 mg. This helps patients reach a therapeutic dose level more quickly, helping to prevent early withdrawal symptoms and improve treatment retention.

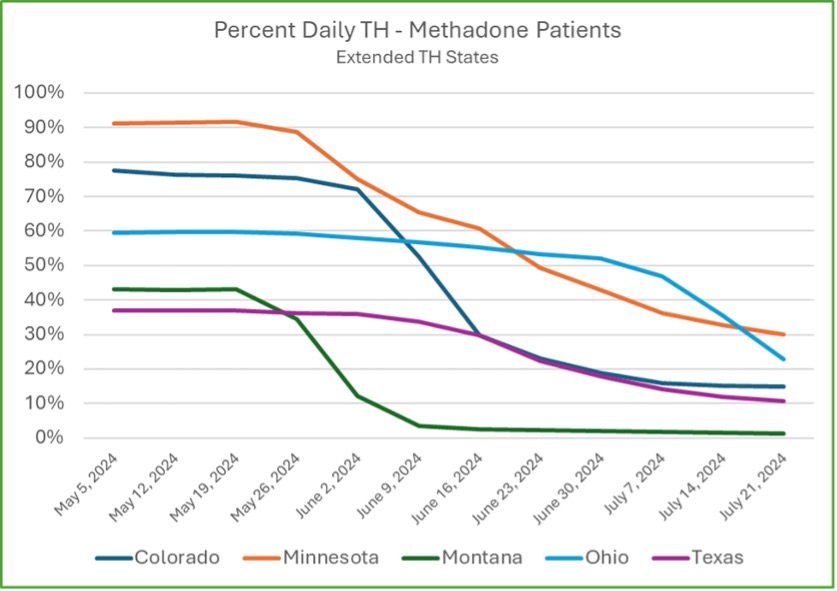

Since CMS operates in 13 states, there is variability in how we can apply these new regulations. Some states have more restrictive rules that prevent the full implementation of SAMHSA’s updates. For instance, not all states allow higher initial methadone dosing or extended take-home doses. However, in states like Montana, which was the earliest to fully implement these changes, fewer than 5% of patients come in more frequently than three times per week. The goal is for other states to reach this same level of flexibility and patient autonomy as regulatory changes allow.

Early Results: Improvement in Treatment Retention

Though the SAMHSA Final Rule changes are still being implemented across various states, early data from Community Medical Services indicates that these updates are already contributing to improved patient retention. Retention is a critical measure of success in opioid treatment programs, as more prolonged engagement in treatment typically leads to better long-term outcomes for patients battling opioid use disorder.

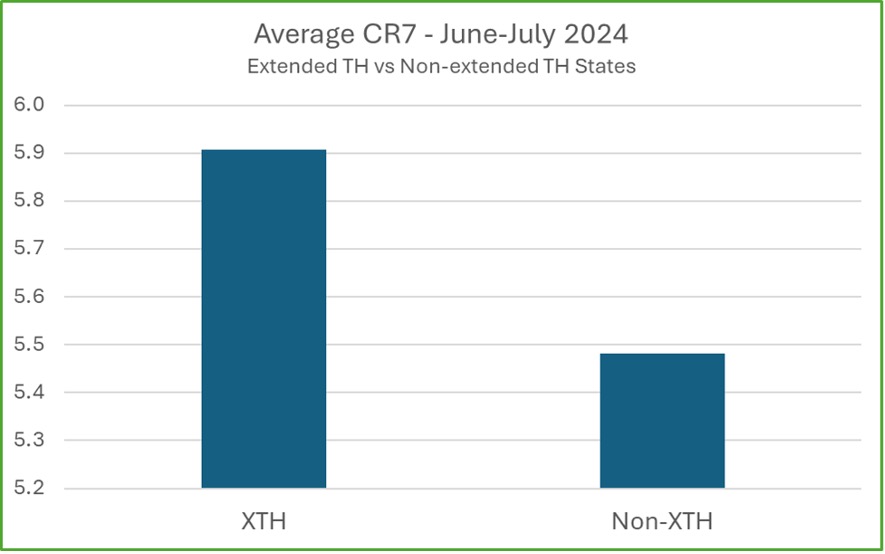

Early data shows a significant improvement in short-term retention in states where extended take-homes (XTH) are allowed. The CR7 (clinical dosing count in the first seven days) is an early indicator of longer-term retention. This metric closely correlates with retention over longer periods. It has shown higher CR7 averages in states that have implemented extended take-homes.

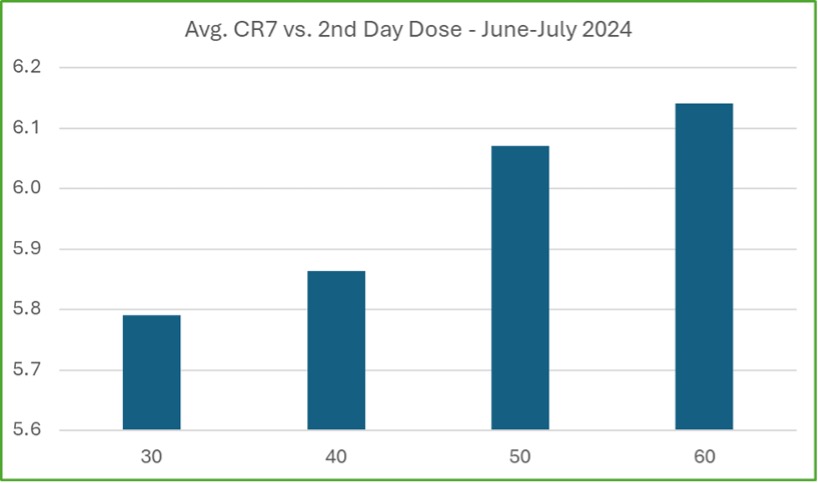

An important factor in improving patient retention is the higher initial dosing now allowed under the new SAMHSA guidelines. In states where this is permitted, early data shows patients are stabilizing more quickly, leading to better retention rates. This is particularly important as opioid tolerance is higher, especially with fentanyl use, making it critical for patients to reach therapeutic doses faster.

Higher doses help reduce withdrawal symptoms, which can otherwise cause patients to drop out early. CMS has started collecting data on the link between higher initial doses and retention, with early results showing a positive relationship. Patients receiving 50 mg or more on the second day of treatment have higher average CR7 scores, indicating they are more likely to stay engaged during the crucial early weeks of treatment. Although this is still early data, it shows promise that these changes are helping to keep patients in treatment longer.

Although these early results are encouraging, it will take time to gather enough data to assess the full impact of the SAMHSA rule changes on long-term retention. As more data becomes available, CMS will continue to analyze these trends to confirm whether these initial positive outcomes are sustained over time. Nevertheless, the early indicators point to these changes making a meaningful difference in improving access to and retention in opioid treatment.

Early Success in Implementing SAMHSA’s Final Rule at CMS

The SAMHSA Final Rule represents a long-overdue update to opioid treatment regulations, and early results from Community Medical Services show that these changes are already making a positive impact. By increasing take-home doses, allowing higher initial methadone dosing, and revising the interpretation of urine drug screens, the rule changes reduce barriers to treatment and improve patient retention.

CMS has worked diligently to implement these changes in the states where they are permitted. For patients, this means fewer trips to the clinic, quicker stabilization with higher doses, and a more supportive approach to managing their treatment. The result is greater patient flexibility and improved outcomes, with early data suggesting that retention rates are on the rise.

Though it is still early, the initial signs are promising. As CMS continues to collect and analyze data, we expect to see further confirmation that these regulatory changes are helping to keep more patients engaged in their recovery and improving their chances of long-term success. While there is still much work to be done, these updates represent a significant step forward in making opioid treatment more accessible, effective, and patient-centered.

If you or a loved one is struggling with opioid use disorder and are looking for support, CMS is here to help. Explore our treatment options and find a nearby clinic to start your recovery journey.

About the Author

Dr. Robert Sherrick was appointed as CMS’s first Chief Science Officer in 2023, transitioning from Chief Medical Officer, a role he served for years.

Prior to serving CMS he had experience working at an inpatient addiction treatment facility in Montana, Pathways Treatment Center, treating all forms of Substance Use Disorders and dual diagnosis patients. Dr. Sherrick has been providing Medication Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder since 2003, initially in an office setting using buprenorphine and subsequently with methadone in Opioid Treatment Programs.

He established a state-wide buprenorphine treatment program for VA Montana with an extensive focus on telemedicine. He is board certified in Addiction Medicine through the American Board of Preventative Medicine and is the Immediate Past President of the Northwest Chapter of the American Society of Addiction Medicine.

Dr. Sherrick received his MS and BS degrees in Electrical Engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and his MD from George Washington University Medical Center.

Start the conversation

Related Content

Dispelling the Myth: Why Methadone for Opioid Use Disorder is Not “Trading One Drug for Another”

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) saves lives, reduces overdose risks, and helps people thrive. Learn how MAT is not just “trading one drug for another.”

How Long Do Opioids Stay In Your System?

Opioids are a type of drug many people use to relieve pain. They can also be highly addictive. Find out how long opioids stay in your system from Dr. Sherrick.

Long-Term SDOH Outcomes

With nearly two years of data, we’re seeing positive outcomes for patients who stay in treatment long-term. Explore the results of our study with Dr. Sherrick.

0 Comments